FSFC: A new financial architecture for anticipating hunger

Chief Economist

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

Agrifood systems are subject to numerous simultaneous risks that are continually growing more interconnected and outstripping the capabilities of conventional aid and financing structures. The challenge is to ensure that mechanisms continue to operate when all else fails; that harvested crops continue to reach markets; that farm income does not collapse; and that shocks do not curtail access to food.

Disruption of agrifood systems directly affects the quality, quantity, and stability of food supplies and hence of nutrition, income, and international security. Some 733 million people face hunger, and that figure shoots up when production systems break down (FAO et al., 2024). Ironically, the people most affected are the very people who support those systems: crop farmers, fishermen, livestock farmers, and especially rural women, whose incomes fall as costs rise and support dries up.

Globally, climate shocks cause agricultural losses amounting, on average, to 123 billion dollars each year, the equivalent of 5% of world agricultural GDP (FAO 2023b). Climate impacts are not only growing more and more frequent and severe, they are also deeply unequal, hitting the most vulnerable countries and communities with the least resources to defend themselves the hardest.

In this situation, safeguarding food security is also a stabilisation strategy. Agrifood systems provide direct and indirect economic support to 3.8 billion people and employ nearly a third of the world’s population. In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, 66% and 73% of women work in the sector, respectively (FAO 2023c). The collapse of these systems means not only food losses but also job losses, breakdown of the social fabric, and macroeconomic risk. When food production is disrupted, poverty, forced migration, pressure on basic services, and in many cases political instability all rise sharply.

Food security is still the main driver of human needs worldwide. But at the same time it is the area where smart, well-designed, anticipatory financing can have the most impact.

The FSFC (Financing Facility for Shock-Driven Food Crises) is a financing platform designed to enhance responses to food crises by combining public and private financing through reinsurance markets and scientific forecasting models and has been launched with this in mind. The goal is to strengthen the anticipatory capabilities of the countries, to ensure suitable resource allocation, and to expand coverage for different kinds of threats, including those that have not been insurable up to now. By integrating different sources of funding in a layered architecture, the FSFC makes it possible to take faster, more precise, scalable action when agrifood systems come under threat (FAO 2024).

The anticipatory action, rapid response context

In a Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) framework, anticipatory action (AA) and rapid response (RR) are essential elements in curtailing the size of food and humanitarian crises. Each has its own role in ensuring effective intervention at each stage of the disaster cycle.

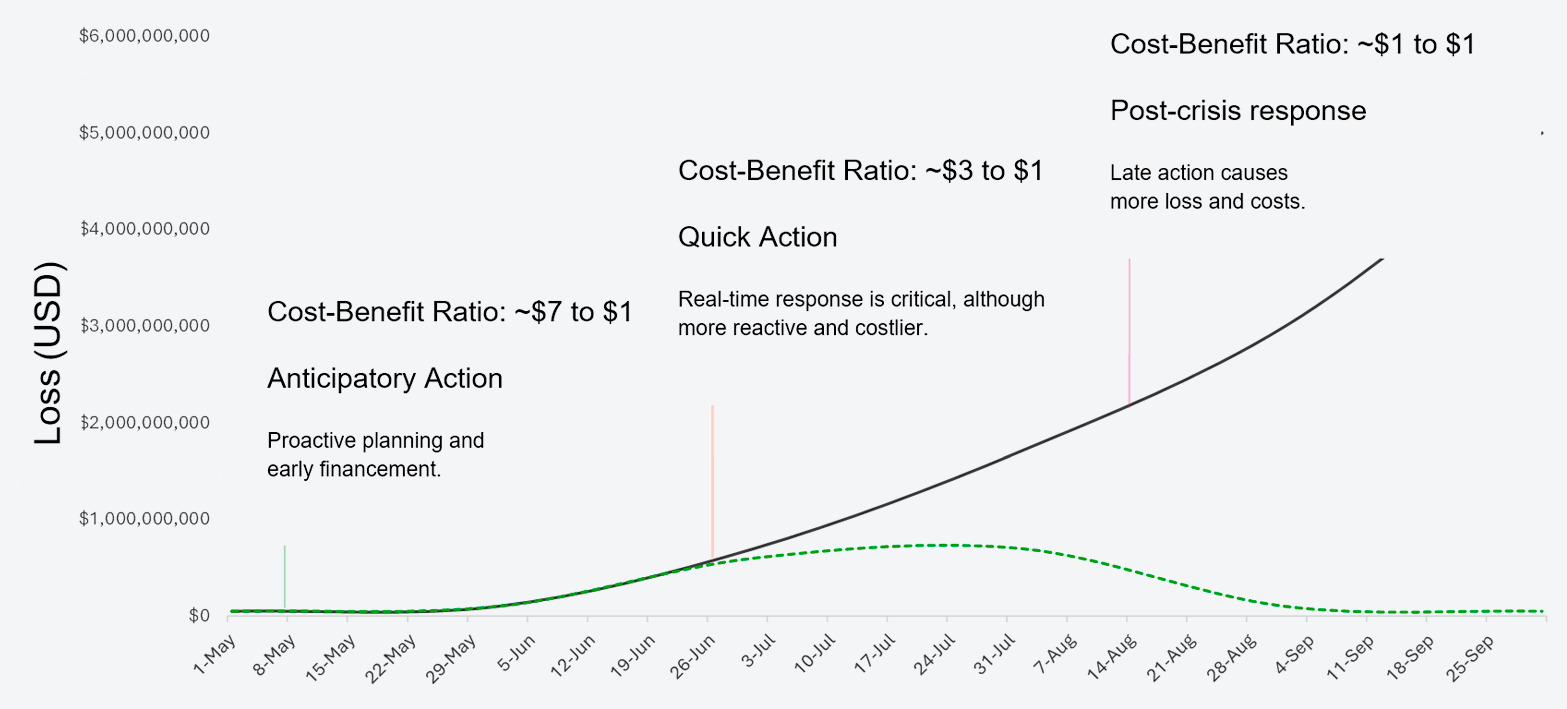

Rapid response (RR) rolled out when a sudden or slow-onset disaster is in progress has a cost-benefit ratio of around 3 to 1. This strategy entails using rapid response funds in the early stages of a crisis and immediately directing resources to mitigate the impact of a shock. In some cases, these funds may be extended for a few months after the crisis to boost early recovery (FAO 2023a).

By contrast, anticipatory action (AA) focuses on acting before the anticipated risks have materialised to prevent or reduce acute humanitarian impacts before they can affect people and their livelihoods. The worth of this strategy is made clear by its cost-benefit ratio, ranging at around 7 to 1, which means that every dollar spent on anticipation can yield major returns by preventing the most severe repercussions of a disaster. The window of opportunity for AA is from the time early alerts warn that a risk might occur to when the actual event takes place, a time frame in which resources can be mobilised in advance to minimise the destructive effects of a shock before it exerts severe effects on communities (FAO 2023a).

Figure 1. Anticipatory action delivers financing before a crisis, saving lives and money.

Source: FAO.

The four interconnected pillars of anticipatory action are: First, defining triggers based on predictive models and early warning systems; second, a flexible financing mechanism that ensures fast allocation of resources; third, taking anticipatory action –making cash and agricultural inputs available and reinforcing infrastructure – to mitigate impacts before the hardest blow hits; and lastly, a cycle of monitoring and compiling evidence to assess the results achieved and obtain feedback for the continuous improvement of protocols. All this is shaped into an Anticipatory Action Plan with specified alerts, pre-approved actions, and a role for each participant, to assure a coherent and effective response to food security challenges.

The benefits of anticipation and rapid action have been well documented. During the floods in Bangladesh in 2020, forecasting models were used, which made it possible to activate transfers of 53 dollars to 23,000 families a week in advance, appreciably reducing agricultural losses and improving food well-being. Even small amounts dispensed in time proved to have positive effects on household consumption and coping ability. A similar anticipatory response in the face of new flooding in 2021 was not only faster but much more efficient, costing half the response in 2019, when help arrived more than 100 days after the worst of the emergency had passed (Hill et al., 2021).

Despite the success of anticipatory action programmes, their implementation remains limited because of a chronic dearth of funding. Of the 51.7 billion dollars requested for global humanitarian aid in 2022, less than 1% was earmarked for anticipatory actions, only a fraction of which were actually implemented. The scarcity of resources prevents long-term planning and deprives many countries of a minimum capability to engage in preventive response.

The good news is that anticipatory action programmes are on the rise. In all, 107 active frameworks were recorded in 47 countries in 2023, with advance commitments of 150 million dollars, up from 137.6 million the year before, and a total of 198 million dollars was mobilised in 93 activations that benefited 12.8 million people. This advance was possible thanks to the coordinated efforts of numerous mechanisms in existence, including the UN’s CERF, PMA trust funds, and the resilience fund of the FAO, Red Cross, and networks like the Start Network (FAO 2024 and WFP & FAO. (2023)).

Even so, there is still a window of opportunity to expand these programmes' coverage. Most current frameworks focus on just a few weather risks, drought, cyclones, and floods, and are designed to be activated to meet individual threats, restricting their ability to respond to serial or compound crises. Many of the threats affecting food security today, e.g., conflicts, political crises, and attacks by pests, remain outside the scope of operations.

Expanding the insurability of risks

One of the core features of the FSFC aimed at supplementing and improving outlooks for anticipatory action and rapid response is to gradually expand coverage of the risks that cannot be insured using conventional products. The platform will therefore be developing a series of standardised products combining high geospatial resolution with information on the exposure of vulnerable populations. This includes designing forecast insurance capable of initiating early disbursements based on objective data even before a shock comes about.

The risks covered by the FSFC are organised according to their return periods (RPs) based on frequency and severity. For instance, an event with a 5-year RP has a probability of occurrence of 20%, while one with a 100-year RP has a probability of only 1%, though it requires greater financial coverage. Based on that approach, the FSFC structures its response into layers: the most frequent events with the least impact (an RP between 5 and 25 years) are covered using cash funds activated as if they were insurance. The most extreme events (an RP longer than 25 years) are covered using reinsurance, enabling large losses to be covered without depleting the base capital.

In addition to supporting anticipatory action and rapid response for recurring events, this layered architecture makes it possible to deal with more complex scenarios, compound events, unexpected conditions, uninsurable risks, and gaps in coverage.

This enables coverage for drought, cyclones, heavy rains, floods, earthquakes, pandemics, teleconnections (ENSO), heat waves, volcanic eruptions, locust infestations, political risk, and conflict to be expanded.

FSFC architecture: Mechanisms and layers of protection

The FSFC combines two financial mechanisms that work together to ensure anticipatory responses to food crises differing in intensity using instruments suited to the level of risk. This architecture relies on two pillars that complement each other: the Multi-Donor Trust Fund (MTDF) and the Working Capital Account.

The MTDF pools contributions from governments, multilateral development banks, and foundations and organises its resources into four layers:

A first layer provides effective financing to match funds already committed under existing anticipatory action frameworks, especially for frequent, low severity events like those occurring every five years.

A second layer serves as a supplement for situations not envisaged in the original planning, such as uninsurable or compound events or unanticipated conditions.

A third layer uses cash to cover moderate risks with a frequency of between 7 and 25 years, activated based on triggers similar to those for parametric insurance.

Finally, a fourth layer provides protection from large-scale catastrophic events with a return period greater than 25 years through policies purchased on international reinsurance markets.

The Working Capital Account reinforces this structure by ensuring continuous liquidity over time. It is funded by initial contributions and is managed based on low-risk criteria. It invests in insurance assets and reinvests its returns in the MTDF. Its key purpose is to provide support for the first, second, and third cash layers, the layers for addressing moderate risks, without depleting the base capital, to ensure financial stability and predictability.

This layered system maximises the impact of each dollar invested. Covering the moderate risks with a return period of between 7 and 25 years with cash avoids the high cost of taking out insurance for that layer. These savings enable more resources to be spent on reinsurance for extreme events.

By way of example, an allocation of 53 million dollars to the cash layer can leverage up to 745 million in reinsurance for events with a return period between 25 and 100 years at a premium of 7.11%. Expanding coverage to include risks with a 50-year return period can mobilise up to 1,161 million at an even lower premium. This combined approach of using cash for frequent events and insurance for extreme events lowers costs, increases response capabilities, and provides the basis for a sustainable, scalable system for anticipating food crises.

Science-based triggers and multi-risk coverage

One of the main bottlenecks in responding to food crises is the lack of mechanisms for activating resources precisely when they are needed the most. Doing this is difficult because of the technical complexity involved in anticipating shocks. It calls for combining climate, agricultural, economic, and social data and turning them into reliable operational triggers. Anticipating shocks requires integrating all the data and deriving reliable operational thresholds, something that few institutions are capable of doing.

The FSFC is supported by a network of technical and operational partners led by the FAO, the World Food Programme (WFP), and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in association with research centres and participants in the reinsurance sector like Munich Re, which bring their experience to bear in modelling, assessing exposure, and designing risk-based financial products. Together they develop evidence-calibrated predictive models tuned to actual risks, not discretionary decision-making.

The FSFC turns that technical capability into a specific financing tool. Its automatic, predictive model-based activation system releases funds on detecting an imminent risk like a drought, cyclones, or conflict.

Example: Population-based triggers in Haiti

Using time series analysis of historical wind intensity and population exposure data, the FSFC sets payment thresholds based on the number of persons affected by category 3 or higher tropical cyclones. In this case, disbursements are activated when a storm impacts more than 500,000 people, an objective threshold based on decades of weather and demographic data. This approach removes the discretionary component and ensures that funds are released predictably and automatically when certain criteria have been met, enabling action to be taken before impacts can scale up.

Between 1963 and 2016 Haiti was hit by at least six large storms that would have activated FSFC payments using this method. Storms like hurricanes Flora (1963), Inez (1966), and Matthew (2016) have exposed more than a million people to high winds and demonstrate the recurring nature of these shocks. According to the FSFC model, each of these events would have activated a 50% payment, providing liquidity in advance to mitigate losses, protect livelihoods, and buttress access to food. This example shows how science-based triggers can be adapted to each country’s specific risk profile, turning historical vulnerability into a basis for operations to ensure a faster, more precise response.

Agile governance with institutional support

FSFC was launched with solid political and institutional support. The platform was given official backing by the leaders of the G7 at the Apulia Summit in 2024 and ratified by the Development Ministers in Pescara, firmly positioning it as a priority instrument for preventing food crises before they can escalate. This backing adds to the mechanism’s legitimacy and brings it visibility at the main international cooperation forums.

The FSFC is hosted by the FAO, which has integrated it into its operational infrastructure, so that it benefits from its technical scope, experience in food security matters, and its inter-agency coordination capabilities. This institutional underpinning helps it link up with existing programmes and ensures that financial flows are aligned with global resilience and humanitarian response frameworks.

One thing that sets the FSFC apart is its Situation Room, a physical and digital space operating in real time to monitor evolving risks, display covers that have been activated, and supervise resource allocation. The Situation Room operates as a technical facility for coordinating with the FAO, implementing agencies, donors, and insurance partners to provide operational transparency and fast response capability.

This system of governance has been designed to be nimble, technical, and functional. Executive and technical committees staffed by specialists in climate risk, food security, and finance are to be set up with pre-approved budgets so that they can authorise disbursements within hours after a data-backed trigger has been activated. This structure removes the bureaucratic bottlenecks that historically have held back responses to allow resources to arrive in time, when they are most needed.

The FSFC represents a new standard for food crisis funding blending science, insurance, and private and public funds to anticipate impacts before they become full-blown emergencies. With its multi-risk coverage, automatic activation mechanisms, and self-sustainable financing architecture, the platform is well suited to fast, precise, and scalable action. At a juncture where crises are constantly becoming more complex and more frequent, investing in anticipation is no longer a strategic option, it is an operational necessity.

References

FAO. (2023a). Anticipatory Action: Protecting lives and livelihoods before crises. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

FAO. (2023b). The impact of disasters on agriculture and food security: Avoiding and reducing losses through investment in resilience. https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/cd76116f-0269-43e4-8146-d912329f411c(A new window will open)

FAO. (2023c). The status of women in agrifood systems. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc5343en(A new window will open) reducing losses through investment in resilience. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc7900en/(A new window will open)

FAO. (2024). Financing Facility for Shock-Driven Food Crises (FSFC) – Concept Note. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd4251en(A new window will open)

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP & WHO. (2024). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 – Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://doi.org/10.4060/cd1254en(A new window will open)

Hill, R. V., Pople, A., Dercon, S., & Brunckhorst, B. (2021). Anticipatory Cash Transfers in Climate Disaster Response: A cost–benefit analysis of early action. Centre for Disaster Protection. https://www.disasterprotection.org/publication/anticipatory-cash-transfers(A new window will open)

WFP & FAO. (2023). FAO–WFP Anticipatory Action Strategy 2023–2025. Rome: World Food Programme and Food and Agriculture Organization. https://www.wfp.org/publications/fao-wfp-anticipatory-action-strategy(A new window will open)

The FSFC is supported by a network of technical and operational partners led by the FAO, the World Food Programme (WFP), and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in association with research centres and participants in the reinsurance sector like Munich Re, which bring their experience to bear in modelling, assessing exposure, and designing risk-based financial products. Together they develop evidence-calibrated predictive models tuned to actual risks, not discretionary decision-making.