Multi-peril agricultural insurance: 45 years protecting the farming sector

Director of ENESA [Spanish National Agency for Agricultural Insurance]

Introduction

Spain’s Multi-peril Agricultural Insurance scheme has already acquired a long track record as the main tool used by the farming sector to manage the risks farmers have to face. It is intended to meet the need to protect producers, who, because of their highly dependent relationship with the environment, are always at the mercy of adverse weather events, which are becoming increasingly more common in today’s climate situation.

It has now been 45 years since the first Crop and Livestock Insurance Plan in 1980, and between then and now the scheme has changed very little, but at the same time a great deal. It depends on where we look. If we look at the basic structure laid out in the Spanish Multi-peril Agricultural Insurance Act [Ley 87/1978, de 28 de diciembre, de Seguros Agrarios Combinados(se abrirá nueva ventana)] (in Spanish) from 1978 and the Implementing Regulations to that Act [Real Decreto 2329/1979, de 14 de septiembre(se abrirá nueva ventana)] (in Spanish) a year later, the structure of the scheme can be said to have stayed relatively unchanged, showing that the Act was on target and for that reason has been able to remain in force with very few changes up to the present time. At the same time, and this is another of the Act’s strengths, it has enabled spectacular growth of the Crop and Livestock Insurance Plans approved year after year. So from that prism today’s plans are little like the ones approved in the beginning.

In the early years covers were restricted to hail and fire for grain, citrus fruit, tobacco, grape, and apple crops. Today, nearly all farm production activities that are of any agricultural or commercial impact are covered against the main perils that are outside the control of policy holders, weather and climate-related perils in particular.

Over the 45 years that have gone by, the volume of insurance coverage has grown substantially, to an insured capital of more than 18 billion euros in 2024. Still, one aspect that with some exceptions has stayed the same over the course of time is a high level of variability in the degree of penetration of the different lines of insurance. Apart from the banana and tomato crops in the Canary Islands, which are insured in their entirety under group policies, stone and seed fruits, persimmons, and vineyards have also attained high levels of insurance coverage. By contrast, olives, a crop of immense socioeconomic importance over large parts of Spain, are at the opposite end of the spectrum. The reason for this high fluctuation in the level of insurance coverage has always been a topic for discussion in many forums, with a higher or lesser degree of consensus. Some of the reasons that have been put forward are a stronger or weaker perception of risk by insurance takers, the features of the farm, how professional the farmer is, etc.

In this regard, closing the coverage gap is an ongoing goal of all the scheme’s stakeholders. The current climate situation and growing loss rates are raising producers' concerns and increasing the need to protect primary sector production.

The Spanish system in the context of the EU

Spain’s Multi-peril Agricultural Insurance Scheme’s 45-year history is something that should be borne in mind when comparing Spain’s scheme with the schemes in other EU member states. First, Spain’s current scheme dates back to a time before our country had joined the EU, and risk management instruments of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) did not become relevant until relatively recently, so Spain’s farm and agricultural insurance subsidies are financed entirely from domestic funds in line with the requirements of EU rules on state aid to the farming sector, but are not subject to CAP rules.

Second, our country’s lengthy experience with farm and agricultural insurance and the level of development achieved have strengthened a scheme that as things stand today is probably the most advanced scheme in Europe, one that is regarded as a bellwether internationally.

A range of different insurance systems are in place in Europe. Spain’s scheme has from the outset been a mixed public-private partnership scheme along the lines of other member states like France, Italy, and Austria, while other states like Cyprus and Greece have opted for wholly public insurance schemes and still others, like Denmark, Finland, and Ireland, have chosen private insurance-based schemes. In any case, it seems clear that mixed public-private partnership schemes are used in the main agricultural producing countries, not only in the EU but also in non-EU countries such as the United States.

The most salient aspect regarding the source of the public funds for supporting the farm and agricultural insurance scheme is that Spain and Austria use funds that are wholly domestic, whereas the rest of the countries use EU funds to subsidise premiums. As a rule, nearly all the countries subsidise their insurance schemes. Certain countries like Spain, France, Italy, and Austria have high subsidies, though there are other countries that provide no public support or only minimal public support, chief among these being Denmark, Sweden, and Ireland.

To conclude this comparison, buying insurance is voluntary for farmers in Spain, and while the Multi-peril Agricultural Insurance Act does envisage certain cases in which buying insurance can be compulsory, that provision has never actually been enforced. By contrast, it should be noted that insurance is compulsory for insurance companies where policies fulfil certain pre-established conditions. Insurance is also voluntary in most other member states, but there are exceptions, like Greece, Hungary, Poland, and Cyprus, in which farm and agricultural insurance is compulsory.

As already mentioned, there are differences and similarities in the main features of the farm and agricultural insurance in the EU countries. I would go so far as to claim that there are two features that set Spain’s scheme apart from other schemes in Europe and that these are the secret to the success achieved by the Spanish model over the course of the 45 years of its existence.

First, I want to point out the coinsurance arrangements in place for insurance companies, under which the companies accept previously approved insurance policy terms, e.g., the same premium costs, yields, prices, and so on. At the same time, the risk taken on by each company is mutualised and depends not on the level of risk ensuing based on the policies it sells but on its share in the panel of coinsurers. This is a safeguard for policy holders, who are assured that they will be able to purchase insurance without being refused by any company, whatever the type of agricultural output, the region within Spain, or the type of risk involved.

And second, I refer to the scheme’s compulsory public reinsurance arrangement with Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros (CCS) as reinsurer, which is one of the basic linchpins keeping the scheme up and running sustainably. This important mechanism has proved to be crucial throughout the multi-peril agricultural insurance scheme’s lifetime, especially during times when loss rates have been high, when the reinsurance reserves have covered the shortfalls in the premiums collected, the last of these in 2023. It should be noted that in 2023, a year when there was an extraordinarily severe drought, the CCS’s reinsurance function funnelled 466.2 million euros (Source of this figure: Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros' 2023 Annual Report, [Informe Anual 2023] (in Spanish) into the scheme from its reserves.

The complicated situation of late years: stresses and imbalances in the scheme and the need for corrective measures

In recent years, in particular starting in 2017, the insurance scheme entered a period of instability caused by the inability of premiums to cover the rates of reported losses. Except for the multi-peril agricultural insurance scheme’s initial start-up years, there had never been such a protracted time of sustained imbalances as between 2017 and 2024.

This is plain to see if we compare the risk premium/loss rate ratios in the past eight years with those in 2009-2016 and in 2001-2008. Insurance is balanced when the ratio is less than or equal to 100 and is out of balance when that ratio is greater than 100. The imbalance is greater the more the higher the ratio is above 100.

In the eight years from 2001 to 2008, the average value of the ratio was 94.6%, and it exceeded 100 (signifying imbalance) in only three of those years. In the following period from 2009 to 2016, the ratio was greater than 100 in five years, and the average ratio rose to 102.2%. Lastly, during the eight years from 2017 to 2024, only two were in balance, and the ratio was over 100 in six. Including the data for this last period raises the average ratio to 117.4%.

There is no option but to ensure that the farm and agricultural insurance scheme remains sustainable in the future so that this important risk management tool will remain available to farmers who rely on it to keep their farming businesses viable in the face of adverse natural events.

And furthermore, since the multi-peril agricultural insurance scheme has to be kept on the path of stability, at least by setting the results of some years off against others, there is no alternative but to take appropriate steps to turn the trend in recent years around. As is sometimes pointed out in certain circles, the fact of the matter is that multi-peril agricultural insurance is government policy, and this sets it apart with respect to the economic results aimed at by other lines of insurance. That is how it is and how it should be: multi-peril agricultural insurance schemes are heavily subsidised by the government, coordinated by ENESA and supported by a strong public reinsurance scheme that avoids or limits the losses experienced by insurers. Even so, the fact of the matter is also that multi-peril agricultural insurance is still insurance, and as such it is subject to actuarial considerations and to the provisions of general and special legislation and regulations.

As a result, a series of measures have been taken of late to correct for certain inefficiencies and imbalances which have in many cases been in existence for a long time. In addition to specific adjustments carried out for some of the most unbalanced lines, a small number of policy holders with consistently high loss rates, caused either by improper operating methods or because climate conditions where the farms are located are unsuitable for production, have been identified.

This small number of policy holders have been found to account for a high proportion of the compensation paid out by the scheme over the time period considered, far higher than the premiums they have paid in over that same period. What has been done in these cases is basically to limit the covers these policy holders can buy instead of taking the commonly used approach of raising premiums to stabilise the line. This is intended to sidestep the serious problem of adverse selection, in which policy holders with lower loss rates drop out of the scheme while policy holders with persistently high loss rates stay with the scheme. That situation needs to be avoided at all costs so as not to jeopardise the scheme’s sustainability.

Support for the multi-peril agricultural insurance scheme by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food. Shift towards a system of differentiated subsidies benefiting targeted groups

As a general rule, though there is considerable variability among lines, multi-peril agricultural insurance premiums tend to be high, in consonance with the high associated risk. Simply compare the usual rates for other types of insurance, which tend to be amounts per mille, with the rates common in farm and agricultural insurance, which tend to be amounts per cent, particularly for some lines like fruit crops, for which rates can go into the double digits. The first outcome of this is that multi-peril agricultural insurance needs public assistance to lower premium costs, because otherwise many farmers would not be able to afford insurance, and Spain’s insurance scheme would not be what it is today. I have already noted above that farm and agricultural insurance ordinarily depends on strong government support in the largest agricultural producing countries with the most highly developed insurance schemes both within the EU and outside it, for instance, Canada and the United States, for the same reasons as in Spain.

Public subsidies have been made available over the entire lifetime of the scheme in order to lower the cost of insurance significantly and encourage farmers to sign up. This support is mostly provided by Spain’s Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food (Spanish abbreviation: MAPA), which allocates budget appropriations to ENESA as subsidies for farmers who purchase insurance. These subsidies are applied directly as discounts on the premiums billed when the insurance is purchased. Expenditures for subsidies for purchased insurance came to 367 million euros in 2024.

Besides the subsidies paid by MAPA, the regional governments of Spain also provide subsidies within their respective territories on top of the subsidies approved by ENESA. In 2024 the regional governments earmarked 140 million euros for multi-peril agricultural insurance subsidies. The level of support can vary considerably from one region to another.

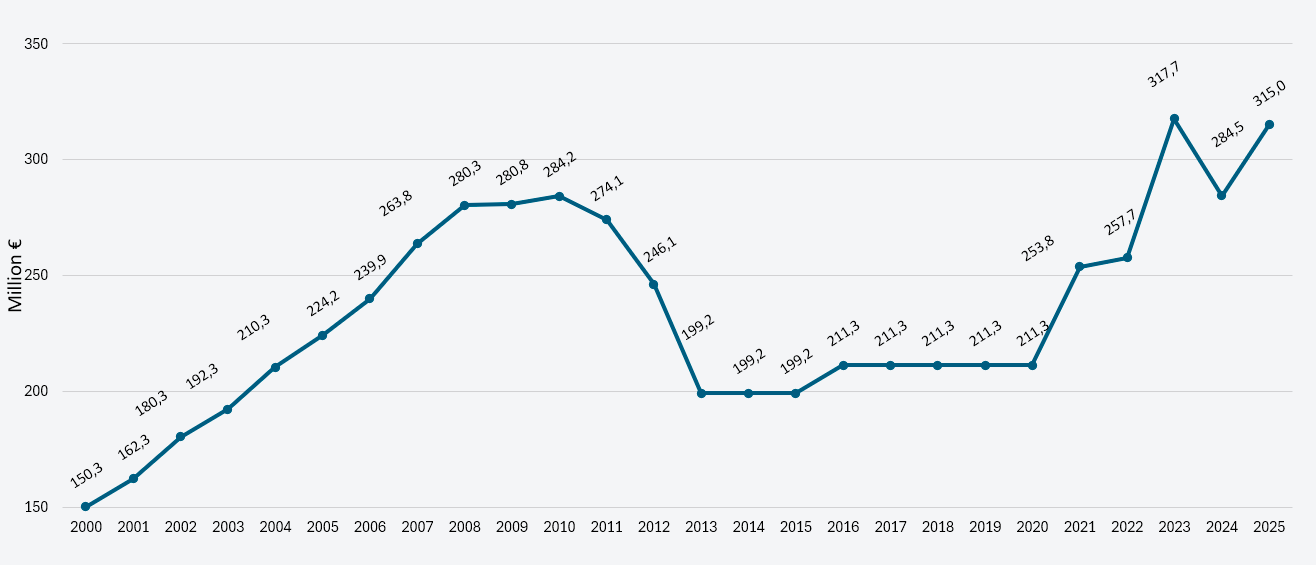

MAPA’s budget appropriations to support multi-peril agricultural insurance have also fluctuated greatly over the years. The Figure below plots the outlays earmarked as multi-peril agricultural insurance subsidies budgeted in the annual plans over the past 25 years. The Figure shows that budget appropriations for this purpose followed a continuously rising trend over the first ten years of this century, peaking at 284 million euros in 2010. After that they dipped considerably starting in 2011, to a level between 199 and 211 million euros in the eight years between 2013 and 2020. A number of increases in this budget appropriation then followed starting in 2021, topping out at 317.7 million euros in 2023.

It should be noted that in addition to the ordinary budget appropriations earmarked in the annual plans at the time, a Spanish Royal Decree-Law [Real Decreto-ley 11/2022] (in Spanish), enacting measures in response to the social and economic repercussions of the war in the Ukraine, approved a special budget outlay of 18 million euros in 2022, bringing the final budget appropriation for that year to 275.7 million euros. Similarly, under that same Royal Decree-Law an additional 42 million euros were added to the budget in 2023, raising the outlay approved in that year’s Annual Plan to 317.7 million euros. In a separate development, because of the severe drought that took place in 2023, a special supplemental allocation of 40.5 million euros was approved by another Royal Decree-Law [Real Decreto-ley 4/2023] (in Spanish), to support farmers who had purchased policies that included drought insurance, bringing the final budget outlay for that year to 358 million euros.

These budget increases in multi-peril agricultural insurance subsidies since 2021 have made it possible to implement major improvements to the scheme, e.g., the extra subsidy for young farmers has been doubled, the basic subsidy has been increased for policies that include supplemental insurance, a new subsidy has been created for jointly owned farms that purchase insurance, additional support has been provided for first-time policy buyers, the support for sheep and goat farms that purchase insurance has been raised substantially, and the basic subsidies for professional farmers, essential farming operations, and members of producers' associations have also been increased.

One of the few amendments that have been made to the Act 87/1978 brought in a special feature turning MAPA subsidies for multi-peril agricultural insurance into immediate grants in the form of discounts applied directly to the cost of the insurance when policies are purchased. This particularly benefits policy buyers by helping farmers with any cash flow problems they might experience if subsidies took the form of subsequent refunds after the fact. This benefit is boosted by the fact that nearly all Spanish Regions have changed their own procedures, so that they too make their subsidies directly available at the time of purchase.

On the other hand, this payment procedure can be a source of sizeable budget shortfalls if, because of unexpected or supervening circumstances, final expenditures in a given year are higher than projected in the budget appropriations approved before the start of the year. In this connection, premium rates and consequently outlays for subsidies have risen, primarily because of substantial price increases of some major farming sector inputs, in large measure caused by the impact of the Ukraine War, combined with higher loss rates in recent years leading to higher premiums and increases in purchases of classes of policies that are more comprehensive but at the same time more expensive, and this has resulted in much higher expenditures than those budgeted in the corresponding insurance plans, making necessary budget amendments to cover the resulting shortfalls. It should be noted in this regard that the budgets approved for 2023 and 2024 were 317.7 and 284.5 million euros, respectively, but expenditures for policy purchase subsidies in those same years came to 401 and 367 million euros, respectively.

This has made necessary an in-depth search for alternatives to help improve decision-making and take into account two aspects that have opposing outcomes, namely, reducing expenditures on subsidies to stay in line with the budgets as approved while in so doing avoiding detrimental effects on multi-peril agricultural insurance to prevent the volume of policy purchases from falling.

This has been the reason behind some of the main changes in MAPA’s multi-peril agricultural insurance subsidy arrangements in its most recent annual plans, e.g., implementing measures to differentiate between types of insureds based on subjective criteria to prioritise subsidies for certain groups, for instance, young farmers, professional farmers, essential farms, and sector associations.

Along with this, subsidies have been progressively scaled according to approved subsidy tranches, with percentage variable premium reductions ranging from 10 to 50%.

In any case, the plan currently in effect for 2025 has reinforced the system of dual subsidies begun the year before, positively differentiating in favour of groups viewed as priorities within the farming sector. Accordingly, professional farmers and the owners of essential farms have been granted exemptions from the insurance class subsidy scale that applies for other policy buyers, joining the young farmers and collective associations that had already been exempted from the scale under the plan for 2024.

In addition, under the current plan professional farmers will be entitled to minimum subsidies provided by the national government of 45% of the cost of premiums eligible for subsidies if they purchase class 3 insurance and 50% if they purchase a class 2 policy. The class 2 and class 3 insurance options available to policy purchasers under the scheme are the most comprehensive as regards the covers offered. Class 2 is the option primarily chosen by farmers by far.

The measures approved are indicative of clear backing for generational replacement and farming sector professionals, defined as individuals that earn their main income from farming, who are most affected by the effects of climate change and hence rising loss rates.

Prioritising multi-peril agricultural insurance subsidies for these groups is something that has been requested by professional farmers' associations, and it is one of the support measures MAPA committed to in April 2024.

The multi-peril agricultural insurance scheme will need continued future support in the form of subsidies from MAPA and the Spanish Regional Governments. Implementing required changes and enhancements to the insurance scheme, as has been the case up to now, will continue to be necessary, and this will furthermore have to go hand in hand with measures aimed at adapting to the reality of a changing climate by farmers themselves, all in the interest of ensuring that the multi-peril agricultural insurance scheme will remain available to farmers in the coming years as an effective tool for defending farmers from the detrimental effects of the adverse events that can harm their livelihoods.

In recent years, in particular starting in 2017, the insurance scheme entered a period of instability caused by the inability of premiums to cover the rates of reported losses. Except for the multi-peril agricultural insurance scheme's initial start-up years, there had never been such a protracted time of sustained imbalances as between 2017 and 2024.